by Gabe Valdez

The Marx Brothers. Salvador Dali.

Roll the idea around in your head for a moment. The Brothers who lived on precision in their wordsmanship and comedic timing, written and directed by the man whose entire art movement was based on erasing the connective tissue that linked moments and plots together.

BACKGROUND – THE MARX BROTHERS

It would have been a conjunction of worldwide talents like none other. The Marx Brothers were the pre-eminent comedians of their time. Brothers in real life, and veteran vaudeville performers, between 1929 and 1949 they made 13 full-length comedies together. Five of those films are on the AFI’s Top 100 Comedies list. Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera are both in the top 12.

They involved a unique blend of high wit, social satire, and base slapstick. Groucho was the wit, always ready with a plot and a one liner, Chico the con man, and Harpo the silent clown. Zeppo sometimes played the romantic lead, but left in 1933 to start a wildly successful talent agency.

Across their films, high society characters would be confounded and frustrated by their irreverence while the poor and needy would welcome the brothers with open arms, helping hands, and often celebrate in music. Imagine for a second the profound effect that message had on audiences during the worst depths of the Great Depression.

BACKGROUND – SALVADOR DALI

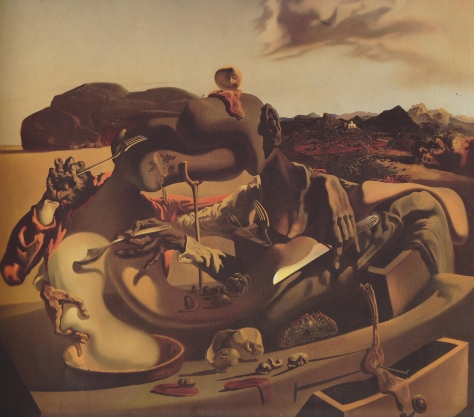

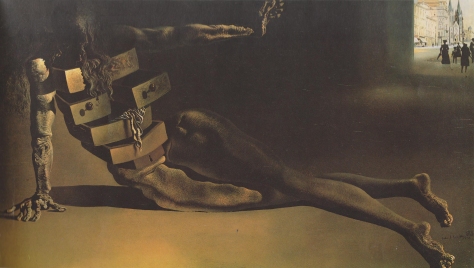

Salvador Dali was a Spanish painter who showed an uncanny mastery of a variety of forms but became a champion of the Surrealist movement. Surrealism has changed over the years and become understood as a manner of presenting a skewed reality, but this is perhaps more closely associated with the avant-garde.

What Surrealism means, or more closely meant at the time, was a meeting of two distant realities, often of dream and real life. The biggest difference between Surrealism today and when it began is that Surrealism now is dominated by symbolism. We’ve embraced the concept that everything presented surrealistically must have a reference point, an anchor in the real to which we can trace it back. We’re very Freudian that way.

This runs counter to the Surrealism movement’s intent – the whole point was to pursue the relief of reference points, to achieve and represent a “psychic automatism,” as Andre Breton put it in his first Surrealist Manifesto. Surrealist art was made without “aesthetic or moral concern.”

Art was not to be framed using the artist’s intentions, but rather presented as an irrational moment pulled from the subconscious, to which audiences could apply their own intentions as they saw fit. Dali’s most famous contribution to film would be a short written for Luis Bunuel, Un Chien Andalou.

Dali became the most commercially accepted painter of the movement, perhaps because his images felt so expertly drawn from so many other schools of painting and thus best evoked the feeling of mish-mashed realities. Due to the Spanish Civil War that lasted from 1936-1939, Dali spent much of the late 30s in the United States and Britain, often taking what were effectively painting retreats with wealthy patrons.

THE PITCH

On paper, the match makes some sense. The Marx Brothers’ comedy is regularly absurdist, treating metaphors and colloquialisms as serious matters to be discussed free of their meanings, and taking the dead serious and treating it as nonsense.

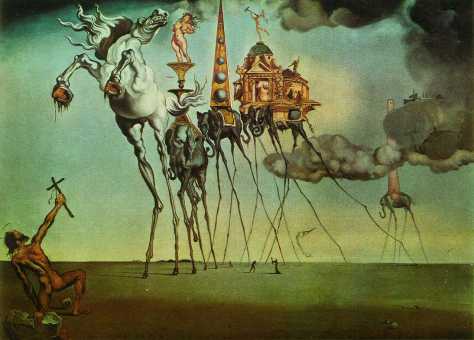

Dali was friends with Harpo Marx, and the two together invented a completely bonkers script. The climax itself would have involved clearing four acres of desert, around which would be lit a towering wall of fire. The Marx Brothers would compete in this arena to see who could ride a bicycle the slowest with a rock balanced on his head. Their audience would be giraffes. Wearing gasmasks. Sitting on bleachers blinded to the contest because of the towering flames. Because surrealism.

Other scenes, according to a surviving copy of the script later described by Harper’s Magazine, involved a dinner party at which Groucho harassed dwarves holding candelabras. The dinner would be interrupted by a great flood that carried with it whining babies, dead oxen, and panicked sheep.

Dali imagined that the great composer of musicals Cole Porter would score the film. “I Get a Kick Out of You” and “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” were his most widely known hits, though Porter would most famously score Kiss Me, Kate in 1947.

WHAT WENT WRONG

To understand this, you have to understand the effect Irving Thalberg had on studio filmmaking. The brothers had left the studio that took them from Broadway to film, Paramount, in 1933. When the Marx Brothers joined MGM, they did so at the persuasion of young phenom Irving Thalberg, who had been made part-owner of the studio and, effectively, vice president in charge of production at the age of 24.

Thalberg codified a great many things – story conferences between cast and crew, live script reads in front of audiences to tighten timing and cut flat jokes, screenings before test audiences to gauge reaction to a film, and reshoots that sometimes changed a film into something entirely new. Earlier, at Universal, he had practically recrafted the studio’s venerable horror franchises and invented the event movie.

Thalberg didn’t demand perfection so much as he demanded improvement, and he often valued the priorities and tolerance of the audience over the vision and intent of the director. This isn’t to say he was divisive; he was almost universally liked. Though he died in 1936 at the age of 37, Thalberg arguably had a more profound effect on how studio movies are made than any other producer before or since.

So when Dali and Harpo came at a post-Thalberg MGM with a nutty script that would’ve cost a fortune, a few things were already afoot.

Firstly, Thalberg’s codes survive until today. Aside from better pre- and post-production processes, Thalberg had also codified certain ways of storytelling. He insisted that films have a low point at which the heroes believe everything to be lost. He championed stories having certain beats that played to the audience. Even had Thalberg survived, it’s difficult to imagine him greenlighting Giraffes on Horseback Salads without severe changes that would’ve made the famously unpredictable Dali walk.

Secondly, the brothers all needed to agree on a film in order to make it. Groucho exerted a great deal of creative control and was the lead voice in dealing with studios and producers. You had to sell your idea to Groucho before you could sell it to the studio. It’s widely rumored that Groucho simply didn’t think Giraffes was funny enough.

Thirdly, Thalberg was the main reason the Marx Brothers had been retained by MGM. Other producers lacked the interest in their comedy. Thalberg’s death was sudden and – despite two very successful films together in A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races – MGM would sever the Marx Brothers’ contract in 1937. This had nothing to do with Giraffes on Horseback Salads.

Matthew Gale, who curated for the Tate Modern, has suggested that perhaps Dali never intended for the script to become a film, but rather the writing of it and – perhaps the rejection of it – was Dali’s ultimate goal for the project.

THE FALLOUT

Remember earlier, when I said the Marx Brothers were a unique blend of wit, satire, and slapstick? You can see their influence across film comedy. Their wit is echoed in the films of Woody Allen and even in the quickfire banter of recent TV shows like The West Wing and Gilmore Girls. Their satire influenced the wide aim of Mel Brooks’ best work. Their influential slapstick can be seen from The Three Stooges to The Beverly Hillbillies to the Farrelly Brothers. The stagey sight gags they popularized live on in everything from The Muppets to The Simpsons. The Marx Brothers didn’t invent these things, but they did show the film world how to use them in the era of the talking motion picture.

Their next film after leaving MGM would be Room Service with the fabled RKO Studios, who never met a film they couldn’t make lose money. The brothers would rejoin MGM and pump out four more films before the United States joined World War 2, at which point the team effectively disbanded. They only rejoined for 1946’s A Night in Casablanca, released by United Artists, because eldest brother Chico was so in debt, though they’d appear together in cameos for TV shows and Groucho enjoyed a second career in so-so films and as a television host on You Bet Your Life.

Nearly all of Thalberg’s production innovations survive to this day. For better and for worse, film is made the way it is today because of his vision for MGM.

The surrealist movement increasingly rejected Dali. While many surrealists were leftist or communist, they became frustrated that their most popular member remained apolitical and believed art should be wholly separated from politics. (Not to put too fine a point on it, but this most closely harbors to creating art without “moral concern.”)

Dali would subsequently be rejected by many surrealist circles for his apolitical stance during a time of politically- and ethnically-driven war. Unlike other artists, he would be allowed to return to – and even championed in – his native Spain. Difficulties with his wife, Gala, later prompted him to buy her a castle where she could reside and he could only visit with written permission. Because surrealism.

Let’s go back to Room Service for a moment. It was a commercial flop and a critical failure, perhaps the Marx Brothers’ worst film. It is notable, however, for featuring a young Lucille Ball. I’d happily make the argument that she’s the only comedian who’s had more influence on screen comedy than the Marx Brothers, effectively inventing the sitcom and modern television production practices.

In I Love Lucy, she would repeatedly pay tribute to the Marx Brothers, embodying in turn each of their mannerisms, style of physical comedy, and at various points dressing up as each of them.

Giraffes on Horseback Salads never really had a chance of being made. It survives only as an academic what-if. But few films, made or unmade, carry quite the potential to merge the visions of such singular and precise, yet completely irreverent and absurdist talents.

Best Movies Never Made is sort of a Throwback Thursday, except for the Thursdays that never happened. It will appear every other week, alternating with Vanessa Tottle’s Silent All These Years. Our previous installment was a rundown on Gladiator 2.

Great column! Your discussion of Thalberg’s influence on modern film makes a lot of sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I hadn’t realized quite how hands-on he’d been with so many famed productions. I think a future article focusing more on how he shaped modern film is a possibility.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Lair of the Lost Films and commented:

A look at the never made surrealist collaboration between The Marx Brothers and Salvador Dali.

LikeLike