There were just too many good articles this week. Thursday’s Child expands on yesterday’s Wednesday Collective.

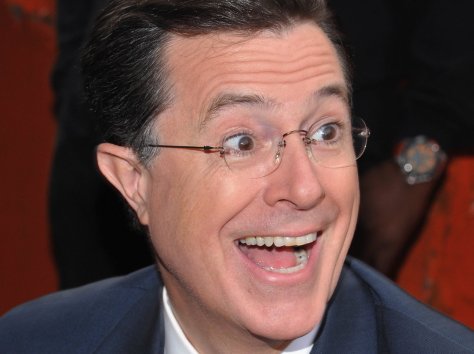

“On Stephen Colbert, Satire, &c.”

Chris Braak

Last week, satirist Stephen Colbert put himself in hot water when his show, The Colbert Report, tweeted an offensive remark about Asian-Americans. It was part of a larger bit in which he criticized Washington Redskins owner Dan Snyder by portraying other cultures in ways similar to how Native Americans are portrayed by Snyder and his team. It was a way of trying to get people of other cultures to identify with the public struggle to change the team’s name.

Needless to say, Twitter doesn’t lend itself the context of a several minutes-long comedy routine. In a vacuum, the offensive remark just seemed offensive, and lost its entire point. Was it brave? Was it foolhardy? Thankfully, I don’t have to answer these questions. Chris Braak at Threat Quality Press (author of that stupendous Wonder Woman piece a few weeks ago) already has. He twists himself in logical loops that amuse, edify, and speak to some rather poignant truths.

The Greatest Actor

Johanna Schneller

There’s a point in Life of Pi that breaks your heart. If you’ve read or seen it, you know it, that rare moment so many artists seek to evoke by breaking the viewer into his or her component parts, by making you see yourself and your life from the outside, in the simplest of terms. It is fulfilling and scary and belittling and majestic. It’s like seeing yourself for the first time, all else removed. It is, perhaps, my favorite moment in all of film, and even thinking of it now, it makes me falter.

It is the achievement of director Ang Lee, novelist Yann Martel, and screenwriter David Magee, among many others. It is delivered in the most unassuming terms by actor Irrfan Khan. If you asked me to tell you the best male actors working today, I wouldn’t get past his name on the list. The honesty of his performances is defined by a quote he gives Canada’s Globe and Mail about his boyhood shyness and inability to express himself: “I remember feeling, ‘I’m not what you are thinking, there’s somebody else inside of me.'”

The article starts with a little too much fandom, but once it settles down, it’s revealing: Khan describes seeking a mystical experience through his acting, and it translates to the viewer in every nuance. His is a quietly forthright performance style that inhabits a scene’s space and transcends across the medium to audiences in a way I’ve never seen before.

Write About the Filmmaking

Matt Zoller Seitz

Music criticism long ago degenerated into celebrity revue and lifestyle reporting. It’s one reason Consequence of Sound is just about the only music review website I’ll still go to – their critics talk about instrumentation, theory, and how they play into theme and emotional effect – they actually analyze the music itself.

Point is, there’s an interesting article about how film criticism has largely devolved into literary analysis. It’s better than celebrity revue, but there’s a good point to be made here – criticism of anything demands some expertise in the field’s theory. Otherwise, it just devolves into that dreaded good-bad scale I’m always railing against. Critics ought to be translators, not because viewers are too stupid or uneducated to understand what’s being said (they aren’t), but because we’re trained in the film grammar to not just describe a movie’s message, but expand on its very technique.

“Imagine, for a moment, football commentators who refuse to explain formations and plays,” critic Sam Adams writes. “Or a TV cooking show that never mentions the ingredients.”

Now, I don’t have to imagine that first part – I’ve heard Troy Aikman broadcast. By “film grammar” I don’t mean knowing some verbiage others don’t, I mean understanding form history and the unspoken language of visual techniques based in everything from art history to statuary to graphic novels. The challenge is to take that morass of intellectual study and translate it into something practical and useful for the widest range of readers.

Criticism, in this day and age, should not simply describe what’s in front of us, it should seek to create new pieces of art based on the pieces of art we critique – to do our best to expand minds, evoke emotion, invoke social consciousness, make caring connections with our readers, and to share information rather than hoard it like some elitist knowledge connoisseur. Do that, and critics earn that the literary analysis may one day be done on our reviews, and not on movies themselves.

Sam Adams’s comments expand on Ted Gioia’s in a piece by Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com, because apparently this article lacked a sentence with 50 names in it.

The Art of Color Grading on The Grand Budapest Hotel

Beth Marchant

A colorist is someone who goes through every scene and shot of a film with its director and editor in order to make sure the coloration is perfect and consistent. You can imagine one of the most exacting directors in this field is auteur Wes Anderson. “Digital Intermediate Colorist” (think: Color Magician) Jill Bogdanowicz recently completed the color grading on The Grand Budapest Hotel, and Beth Marchant at Studio Daily puts her through her paces in this exhaustive interview. It gets technical at points, but always returns to the creative aspect of a crucial job most don’t even know exists. It’s completely worth diving into, especially for filmmakers and photographers.

Thelma Schoonmaker on Editing

Nick Pinkerton

Martin Scorsese’s go-to editor, Thelma Schoonmaker, discusses the craft of editing with Film Comment. She addresses editing for performance over continuity, how to edit improvised scenes, and the matter-of-fact, jump cut style she employs on The Wolf of Wall Street. This is a must-read for filmmakers.

The Alien Soundscape of Scotland

Trey Taylor

It’s rare that I champion a movie that hasn’t come out yet, but Under the Skin is based on one of my favorite novels by Michael Faber. If his name sounds familiar, it’s because he wrote bestseller The Crimson Petal and the White. Add to this the completely strange and unfamiliar ways in which every technical aspect has been approached – the whirlwind rhythm-based editing of Paul Watts, the cinematography of Daniel Landin suggesting a world that exists in some other film’s fade to black, the suggestively post-industrial John Cage-influenced score of Mica Levi…as well as what this article at Dazed Digital discusses: the sound design by Peter Raeburn and Johnnie Burn.

Burn himself wandered Glasgow recording the city’s sounds through a secret microphone hidden in his umbrella, and he discusses the best techniques to nonchalantly shove it in people’s faces as he passes them on the street. It’s a good read, especially for those interested in learning about the single most difficult and overlooked responsibility of any independent film production – sound editing.

The Joseph Gordon-Levitt Bylaw

PivotTV

Yesterday, I introduced The Sharni Vinson Rule: One never needs an excuse to post about Sharni Vinson, the Australian lead of You’re Next and Patrick. I added that – in the interest of equality – the same rule applies to Joseph Gordon-Levitt, star of Looper and the unauthorized biography of every relationship I’ve ever had, (500) Days of Summer.

Down the road a bit, you’ll be reading my thoughts on Gordon-Levitt’s Socratic brainchild of a new show, HitRECord on TV. It is the most important thing on television because it changes the very way TV is created, viewed, analyzed, hosted, and understood. Bold claim? Not after you’ve seen it. Go to the site and see what I mean.

Edited (4/3/14): to reflect that the offensive tweet was on The Colbert Show‘s Twitter account, and not on Stephen Colbert’s.